The Flame

At age eighteen, in the early fall of 1930, Jackson Pollock left Los Angeles and went east, bent on becoming an artist. He had very little going for him other than his vocational fixation - his belief that "being an artist is life itself - living it I mean." This unpromising, uncompromising young man only lived about a quarter of a century longer. At his death, his art was the most consequential and controversial ever to have been produced by American. Reflecting on the immense success of Pollock's work, his brother Sande offered his thoughts on it beginnings, which might, be said, have prompted a kindly counselor to suggest a career switch to tennis or plumbing.

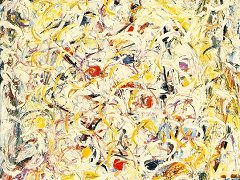

Pollock's most significant early adviser was Thomas Hart Benton, his teacher at the Art Students League, the school in which he enrolled almost immediately after arriving in New York. Although quick to note his new pupil's apparent lack of facility, Benton - insightful as well as kind - saw Pollock's "intense interest" in art and "intuitive sense of rhythmical relation" as the makings of "some kind of artist". Had Benton been able to look into the future at Pollock's works, the then-unimaginable poured and dripped paintings of 1947-50, it is a fair bet that he would have found no more precise words to describe exactly what kind of artist his student had become.

With the advantage of hindsight, we can see The Flame, painted some years after Pollock was no longer under Benton's direct tutelage, as a distant forerunner of the revolutionary canvases to come. While the painting's curvilinear dynamics and contrasts of light and dark retain Benton's expressionist chiaroscuro and Albert Pinkham Ryder's moody, nineteenth-century symbolist effects, their deployment in the service of a quasi-abstract subject whose essence is flickering movement seems to have liberated Pollock for this early experiment in free structure. If the writhing flames seem too thick, too muscular, they nonetheless combine to conflate figure and ground in a centrifugal allover composition. Roughly organized on what would become governing principles in Pollock's "classic" works of almost a decade later, Flame's rude, nearly savage fracture is a far cry from the virile lyricism of the fluidly intertwining skeins and webs of pain to come. Yet, like Paul Cezanne's early, awkwardly affecting the handling of the medium, Pollock's painting exhibits a raw, uncivilized intensity, as if each stroke of the brush were imbued with his own anxiety. Painter Peter Busa's subsequent observation that Pollock could give "painting an organism of existing" is already evident in Flame. More than any other early Pollock, Flame proposes, as its grand successors proclaim, that art's deepest powers are rooted in patterns of energy, independent of representation.