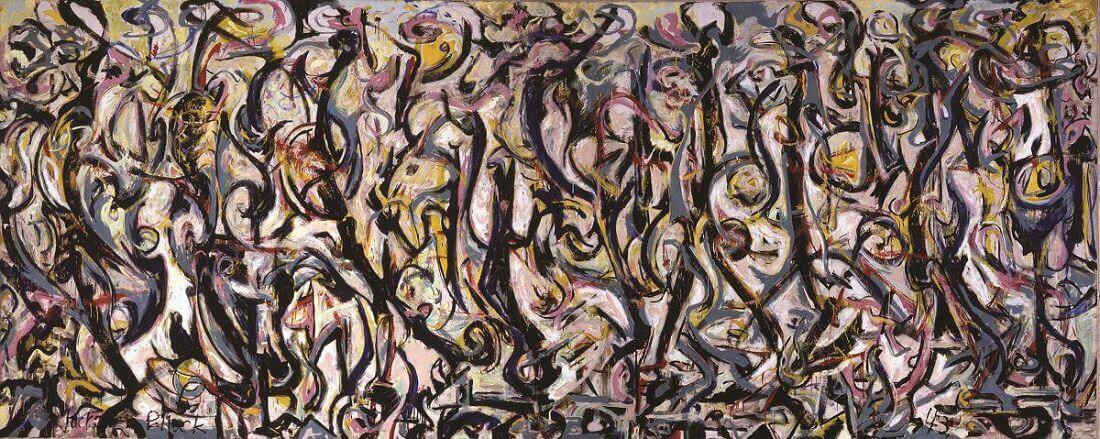

Mural, 1943 by Jackson Pollock

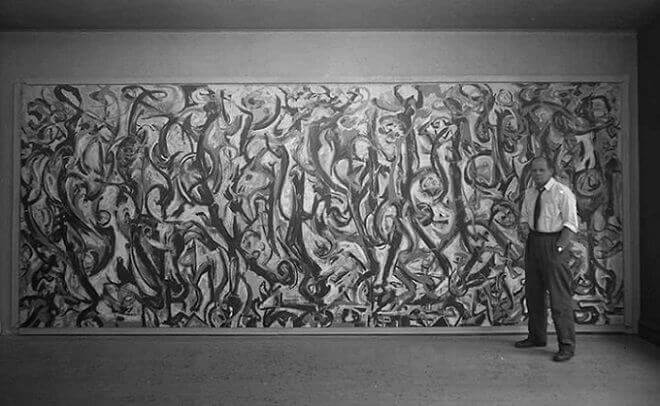

When Pollock received the commission to create a mural for the entry to Peggy Guggenheim's new townhouse, he had Howard Putzel, Guggenheim's secretary-assistant, to thank. Putzel had urged Guggenheim to give Pollock a project that would unleash the force he perceived in Pollock's smaller-scaled easel paintings. For her part, Guggenheim was eager to present in her home a symbol of support for the new American brand of art she was beginning to champion in her gallery. The choice of subject was to be his, and the size, immense 81 1/4" x 19' 10", meant to cover an entire wall. At the suggestion of Guggenheim's friend and advisor Marcel Duchamp, it was painted on canvas, not the wall itself, so it would be portable. Pollock wrote of his commission that it was: "...with no strings as to what or how I paint it. I am going to paint it in oil on canvas. They are giving me a show on November 16 and I want to have the painting finished for the show. I've had to tear out the partition between the front and middle room to get the damned thing up. I have it stretched now. It looks pretty big, but exciting as all hell."

Pollock signed a gallery contract with Guggenheim in July 1943. The terms were $150 a month and a settlement at the end of the year if his paintings sold. He intended to have the mural done by the time for his show in November. However, as the time approached, the canvas for the mural was untouched. Guggenheim began to pressure him. Pollock spent weeks staring at the blank canvas, complaining to friends that he was "blocked," and seeming to become both obsessed and depressed. Finally, according to all reports, he painted the entire canvas in one frenetic burst of energy around New Year's Day of 1944 - although the painting bears the date 1943. Pollock told a friend years afterward that he had had a vision: "It was a stampede...[of] every animal in the American West, cows and horses and antelopes and buffaloes. Everything is charging across that goddamn surface." Pollock's "vision" may have been a memory from his childhood in the American West. While there is some suggestion of figuration within Mural, its overall impact is that of abstraction and freedom from the restrictions imposed by figures.

As soon as the canvas was dry to the touch, Pollock broke down the stretcher, rolled the canvas, and transported both to Guggenheim's townhouse. Some accounts have said that the painting was too long for the space by almost afoot, and when Pollock discovered this he became quite hysterical. Marcel Duchamp and another artist were said to have cut eight inches from one end before it was installed. However, close examination by numerous experts over the years has revealed no evidence of this.

Where Pollock's early works were dark interpretations of Thomas Hart Benton's figurative Regionalism, Mural displays an abstract, expressionist vigor. There are many influences from Pollock's life and studies present in

Mural - Benton's energetic rhythms, the swirling colors of the American artist Albert Pinkham Ryder, and even the harsh blacks of the Spanish Baroque artist El Greco. The work of the Mexican

muralists Diego Rivera inspired him, as did the abstraction bordering on the figurative that originated with the artist to whom Pollock owed the most,

Pablo Picasso. We can also see influences from his Jungian psychoanalysis, from the Native American art he had seen as a child, and from the surrealist technique of automatism, which attempted

to abandon conscious control in order to allow the unconscious mind to guide the hand.

When Pollock painted Mural, he redefined not only the limits of his own abilities but also the possibilities of painting. Pollock's innovation provided a new direction for artist - he had combined the method of easel painting and an

abstract style into the large scale of the traditional mural.

Mural was immediately recognized as a turning point for American art. Art critic Clement Greenberg had written encouraging but less than whole-hearted endorsements in his Pollock reviews, but, he said after he saw the big mural in

Guggenheim's townhouse, "I took one look at it and I thought, 'Now that's great art,' and I knew Jackson was the greatest painter this country had produced." From this point on, throughout the forties, Greenberg was a firm

advocate of Pollock's art, and in turn Pollock's success canonized Greenberg's judgment.