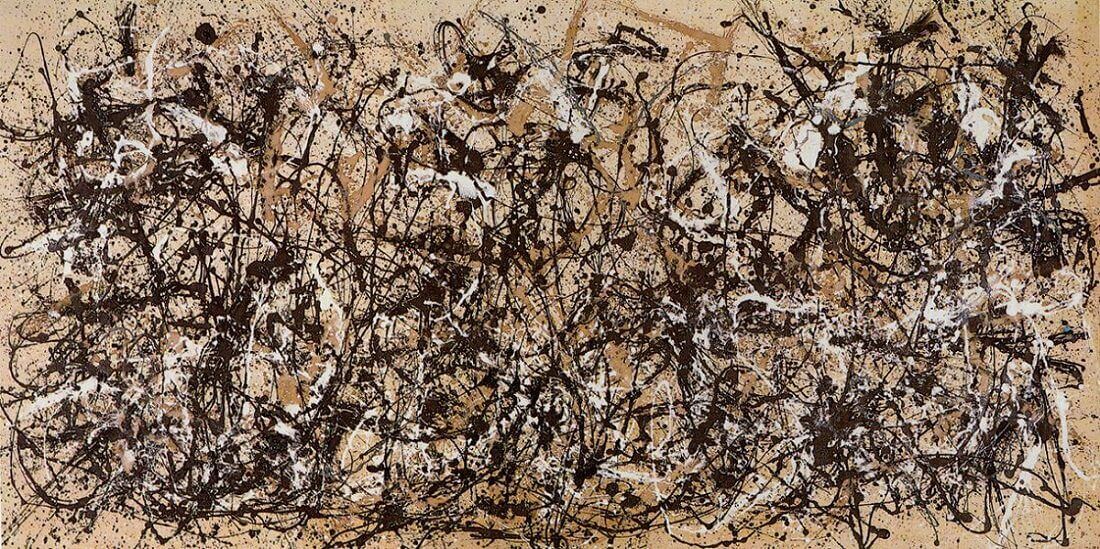

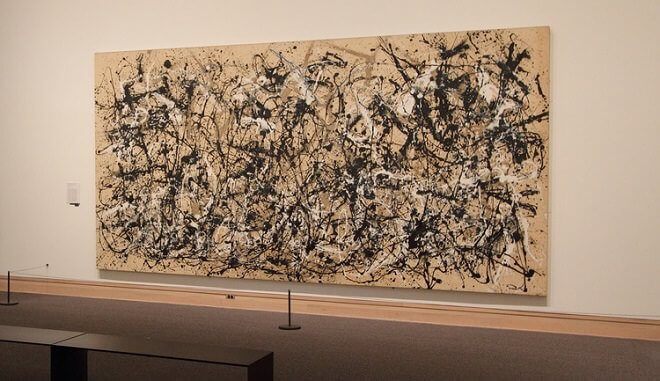

Autumn Rhythm (Number 30), 1950 by Jackson Pollock

Pollock had created his first "drip" painting in 1947, the product of a radical new approach to paint handling. With Autumn Rhythm, made in October of 1950, the artist is at the height of his powers. In this nonrepresentational picture, thinned paint was applied to unprimed, unstretched canvas that lay flat on the floor rather than propped on an easel. Poured, dripped, dribbled, scumbled, flicked, and splattered, the pigment was applied in the most unorthodox means. The artist also used sticks, trowels, knives, in short, anything but the traditional painter's implement to build up dense, lyrical compositions comprised of intricate skeins of line. There's no central point of focus, no hierarchy of elements in this allover composition in which every bit of the surface is equally significant. The artist worked with the canvas flat on the floor, constantly moving all around it while applying the paint and working from all four sides.

I'm very representational some of the time, and a little all of the time. But when you're working out of your unconscious, figures are bound to emerge. Painting is a state of being. Painting is self-discovery. Every good artist paints what he is." - Jackson Pollock

Size is significant: Autumn Rhythm is 207 inches wide. It assumes the scale of an environment, enveloping both for the artist as he created it and for viewers who confront it. The work is a record of its process of coming-into-being. Its dynamic visual rhythms and sensation's buoyant, heavy, graceful, arcing, swirling, pooling lines of color are direct evidence of the very physical choreography of applying the paint with the artist's new methods. Spontaneity was a critical element. But lack of premeditation should not be confused with ceding control; as Pollock stated, "I can control the flow of paint: there is no accident."

For Pollock, as for the Abstract Expressionists in general, art had to convey significant or revelatory content. He had arrived at abstraction having studied with Thomas Hart Benton, worked briefly with the Mexican muralists, confronted the methods and philosophy of the Surrealists, and immersed himself in a study of myth, archetype, and ancient and "primitive" art. And the divide between abstraction and figuration was more nuanced, there was a back-and-forth at various moments in his career.